Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup, featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

The changing sky that plants see

Researchers from Kyushu University have developed a new numerical model to explain the behavior of sunlight under various weather conditions. Unlike previous methods that focused on how plants perceive sunlight as a pure source of energy, this study introduces a metric to quantify sunlight intensity and its influence on plant growth and blooming patterns.

Published in Ecological Informatics, the team hopes their research can benefit the agricultural industry and help farmers make better decisions about crop growth. This advancement is crucial for understanding the variations in plant photosynthesis in response to different sunlight and weather patterns, moreover it may also provide new insight into how changes in cloud cover due to climate change affect vegetation carbon dioxide uptake.

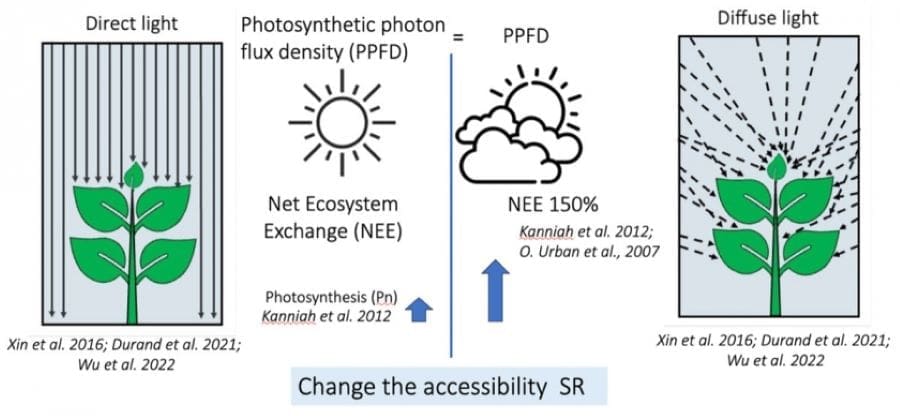

We know plants need the sun to live because it provides the energy for photosynthesis. And while conventional wisdom suggests that the more sun a plant gets the better, it is always not the case. In fact, because of how light is scattered, cloudy weather can greatly benefit a plant’s growth. On cloudy days, sunlight is scattered out more evenly, allowing it to reach lower parts of the plant. In contrast, on sunny days, sunlight energy is stronger but comes from a single direction, causing the leaves on the lower parts of the plant remain shaded, and therefore do not absorb as much sunlight.

“Plants also respond to different wavelengths of sunlight. If you have ever seen a rainbow, you know that sunlight is made up of many wavelengths. Plants sense these different wavelengths of light and alter their growth responses,” explains Amila Siriwardana, first author and PhD student at Kyushu University’s Faculty of Agriculture.

Plants can detect the ratio of wavelengths to understand their surroundings. These ratios are affected by many factors, including atmospheric density, cloud cover, or the altitude of the sun. However, such information had not been categorized in the context of plant physiology and ecology. So, to see how daily sunlight changes during different weather conditions, the research team began a project collecting yearlong sunlight data.

“While many projects look at only the ‘energy’ produced by the sun, our methods set out to categorize both the ‘energy’ and ‘quality’ of light. By sorting sunlight into five categories, from clear skies to overcast, we can better understand how plants can adjust and respond to different light conditions,” adds Professor Atsushi Kume, who led the team.

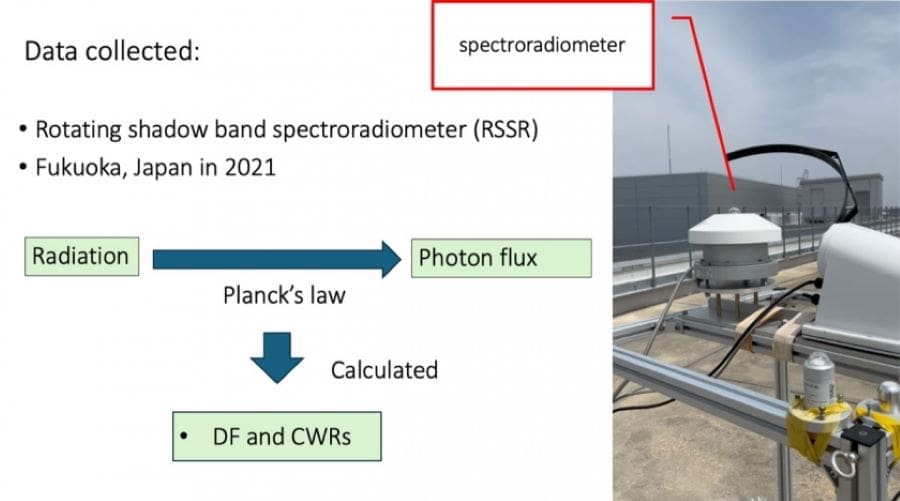

To record sunlight across different times of day and weather conditions the researchers used a device called a spectroradiometer that measures the full spectrum of sunlight. The spectroradiometer was placed on top of Kyushu University’s Faculty of Agriculture building on Ito campus, where it collected data from sunrise to sunset every day in 2021.

Using the collected data, the researchers then developed a machine learning model to sort and predict how sunlight changes. The model works by spotting patterns in weather data such as how much sunlight reaches the ground, how much the light is scattered, how polluted or clear the weather is, and humidity. From these patterns, the model categorized sunlight into five groups on a sliding scale. For example, group one was categorized as a clear sunny day, while group five described overcast cloudy days.

The team noticed that on clear days, like those categorized as group one, more sunlight energy reaches the ground. Conversely, as the sky becomes more overcast, the sunlight energy decreased, but at the same time the scattering of light and the proportion of ultraviolet light increased. Additionally, the color of sunlight shifts slightly, moving from red tones on sunny days to blue tones under cloudy conditions.

Once the numerical model was trained, it could make highly accurate predictions of sunlight patterns using simpler weather data.

“Our method achieved 94% accuracy in predicting sunlight category without the need for expensive advanced equipment,” says Siriwardana. “Our model is especially relevant for regions experiencing four distinct seasons similar to Japan’s.”

“We hope our model can be used to address the challenges in modern agriculture. Farmers can use this information to improve greenhouse conditions and planting schedules throughout the year,” Kume explains. “For instance, during Japan’s cloudy rainy season in June, farmers might adjust their greenhouse operations or crop spacing to maximize available light. Even in the fall and winter, when sunlight patterns change, farmers can adapt their strategies based on our model.”

In the future, the team hopes to expand the model to cover more climate types, such as high-altitude or tropical regions, and further understand how sunlight affects the environment.

Journal Reference:

Amila Nuwan Siriwardana, Atsushi Kume, ‘Introducing the spectral characteristics index: A novel method for clustering solar radiation fluctuations from a plant-ecophysiological perspective’, Ecological Informatics 85, 102940 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.102940

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Negar Khalili | Kyushu University

AI technique boosts climate change defenses

The research is part of an attempt to grapple with the effort to make expensive, long-term investments to mitigate the impacts of climate change. The substantial uncertainty related to long-term climate change makes it difficult for political leaders to make investments now that are designed to protect citizens for decades or longer. The difficulty is enhanced by the vast number of variables that go into any such decision and by the fact that the variables are likely to shift in unforeseen ways.

In an article published in PNAS, the researchers looked at flooding, which has caused increasing damage along the coastal United States and around the world. Governments are building coastal defenses against flooding, but they cannot rely on past conditions to guide defenses that will be needed in the future.

“Defenses are being built to protect coastal regions for the next few decades or longer,” said co-author Ning Lin, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Princeton. “Climate projects are largely uncertain over long time horizons.”

Lin said that to deal with this uncertainty, planners must be flexible and ready to adapt their plans to future observation of climate conditions. Although this is extremely challenging because of the complexity of climate science, Lin said that harnessing advances in data science can provide an effective strategy.

Robert Kopp, a co-author of the study and a distinguished professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Rutgers said uncertainty about the impact of melting ice sheets on sea levels has led to “controversy about how planners should consider the possibility of rapid ice-sheet loss.“

Kopp said that flexible approaches can help communities prepare for worst-case scenarios without paying too much for protection. “Planning for high-end sea-level rise costs a lot, and there’s a good chance it won’t be necessary, but failing to plan for it can be devastating,” he said.

In the PNAS article, the team describes how they simulated efforts to defend Manhattan against sea level rise through the end of this century. The goal was to determine whether any decision-making process that systematically incorporates observations and updating would prove superior to others over such a long period of time. To do this, the researchers simulated decisions by city planners in 10-year intervals up to the year 2100.

The researchers compared their decision-making process with existing methods. For example, using the static method of building a seawall for a historic 100-year flood plus a sea-level-rise projection — as currently applied by New York and other coastal cities — is one method; designing a dynamic seawall that will be increased in height over time according to projected future climate change is another.

The researchers graded each method by its efficiency — the cost of defenses plus the estimated damage caused by flooding. For example, spending $10 million on a seawall that allowed $50 million in property damage ($60 million cost) would be less efficient than spending $30 million on a seawall with $15 million in property damage ($45 million cost).

The researchers found that calculations of a dynamic seawall based on reinforcement learning that systematically incorporates observations of sea level rise over time increased efficiency when compared with other methods (detailed in the paper). Compared with other systems, reinforcement learning lowered costs by 6-36% in a scenario modeling climate change under moderate carbon emissions. For a high emissions scenario, the decrease was 9-77%.

Reinforcement learning is a type of machine learning in which a program makes decisions and receives positive reinforcement based on results. Designers train the program by running it through vast amounts of simulated decisions, and it learns by trial and error rather than through explicit instructions from programmers.

This is essentially the way many AI systems operate. It is particularly effective for situations that are extremely complex and subject to rapid changes over time. Computer scientists have used reinforcement learning to train AI to perform tasks such as playing chess, driving cars, and controlling robots and drones. The method has also been used for large systems used to store power or control water supplies.

For their case study, the researchers looked at defenses proposed for low-lying areas in Manhattan. After Hurricane Sandy caused tremendous damage in New York and New Jersey in 2012, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposed constructing a series of seawalls to defend Manhattan called the Big U. Some sections of the Big U are being built and others are in the planning stage. But a final completion plan for the entire system has not yet been set.

The study looked at proposals for the Big U and how defenses against coastal flooding should be changed to respond to future threats to New York from the sea. Flooding is driven both by sea level rise and storms. Both are affected by climate change, which in turn is impacted by global carbon emissions. The researchers wanted to evaluate decision methods every 10 years and allow for adjusting the Big U to reflect available threat data at each interval.

Because the impacts of climate change over a long period remain uncertain, the researchers wanted to study methods of making the best decisions for future changes with the data available at the time. Traditionally, engineers have built protective systems like seawalls and levees to resist historic floods, building protection from floods that would occur only once in 50 or 100 years. But because the climate is changing, such systems no longer work. Building the Big U seawalls to match the highest storm surge over the past 100 years would leave Manhattan vulnerable as climate change drives higher storm surge levels.

The researchers looked at a number of decision-making methods that take into account changing conditions. Most methods allowed for changes based on key variables and some allowed planners to make future projections that would also influence decisions. For example, as a temporary measure, residents could flood-proof their homes (“accommodate”), but eventually, higher sea levels would necessitate a high seawall (“protect”).

In some cases, a seawall could prove too costly to protect everyone and residents would be encouraged or compelled to leave threatened communities (“retreat”). In a situation with only a few variables to account for, the benefits of a plan can be estimated relatively easily. But uncertain climate change presents an extremely complex scenario. The researchers showed that reinforcement learning can be used to design integrated strategies, including retreating from low-lying areas, protecting property further inland at higher elevation, and accommodating in between, with a 5-15% reduction in cost compared to the one-dimensional seawall strategy.

Lin, one of the lead researchers, said defending Manhattan is not only complex, but it also requires making difficult decisions under uncertain conditions. For each time interval, planners must make decisions based on observed sea level rise and roughly 80,000 scenarios of future sea level rise and corresponding decision reactions. The difficulty of the decisions compounds as the number of intervals increases.

While climate adaptation decisions are not simple, Lin said reinforcement learning is a highly efficient system for incorporating observations and updating plans to derive optimal solutions for limiting impacts from extreme events. Reinforcement learning also outperforms previous methods by avoiding losses induced by uncertain changes in future global carbon emissions.

“The analysis of New York City’s situation is by no means unique,” said Michael Oppenheimer, a study co-author and professor of geosciences and international affairs at Princeton. “The method can be applied widely, although its benefit compared to other systems of analysis would vary from place to place.”

Journal Reference:

K. Feng, N. Lin, R.E. Kopp, S. Xian, & M. Oppenheimer, ‘Reinforcement learning–based adaptive strategies for climate change adaptation: An application for coastal flood risk management’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 122 (12) e2402826122 (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2402826122

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by John Sullivan | Engineering School | Princeton University

Climate change ‘will accelerate’ owing to decline in natural carbon storage

The natural process of locking away carbon dioxide (CO2) appears to be in decline – and climate change will accelerate as a result, a University of Strathclyde study warns.

Researchers found that the levels of CO2 retained in vegetation through this process, which is known as sequestration, had been increasing at 0.8% per year in the 1960s but peaked in 2008 and are now falling at 0.25% per year.

If its growth rate of the 1960s had continued, natural sequestration would have increased by 50% from 1960 to 2010 but if its current rate of decline continues, it will have reduced by half in 250 years.

Cancelling out

Sequestration offsets some of the emissions generated by human activity, which have recently been increasing by around 1.2% a year. Cancelling this out would require these emissions to fall by 0.3% annually – equivalent to around 100 million tonnes of CO2.

The study has been published in the Royal Meteorological Society’s journal Weather.

James Curran, a Visiting Professor at Strathclyde’s Centre for Sustainable Development, co-author of the study with Dr Sam Curran, said: “Most of the Earth’s land mass is in the Northern Hemisphere and, during the northern summer, the abundant vegetation of the north absorbs a huge amount of CO2 from the atmosphere.

“In the northern winter, some of this CO2 is released back into the atmosphere through the natural biodegradation of dead vegetation but a portion remains locked in roots, soil and dormant woody matter. The overall curve of CO2 concentrations still rises year-on-year, owing to additional emissions from human activity.”

He continued: “It’s urgent that every effort is made to rebuild biodiversity and associated ecosystem services, including sequestration. Deforestation must stop; rewilding must be encouraged; forest fires must be prevented. For large-scale habitats, which are more resilient and offer enhanced ecosystem services, defragmentation must be prioritised; fossil fuels must be phased out; timber and fibre products must be reused for as long as possible, as part of a wider circular economy.”

Professor Curran added that there was a widespread belief that sequestration was still increasing but would begin to decline at some point in the future, whereas data showed the fall was already underway.

He said: “It is known that increasing CO2 in the atmosphere acts like a plant fertiliser, while a warming world also allows vegetation to grow more rapidly and easily, particularly in the extensive chilly northern latitudes of Canada and Russia.

“Satellite observations are reported as seeing the Earth becoming ‘greener’ as vegetation spreads. However, that simple assumption is countered by all the other effects which can kick in including damage to vegetative growth by excessive heat, drought, floods, wind damage, wildfires, desertification and potentially wider spread of plant pests & diseases.”

Data for the study was obtained from the Mauna Loa Observatory, sited on the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii.

Journal Reference:

Curran, J.C. and Curran, S.A., ‘Natural sequestration of carbon dioxide is in decline: climate change will accelerate’, Weather 80, 3, 85-87 (2025). DOI: 10.1002/wea.7668

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Strathclyde, Glasgow

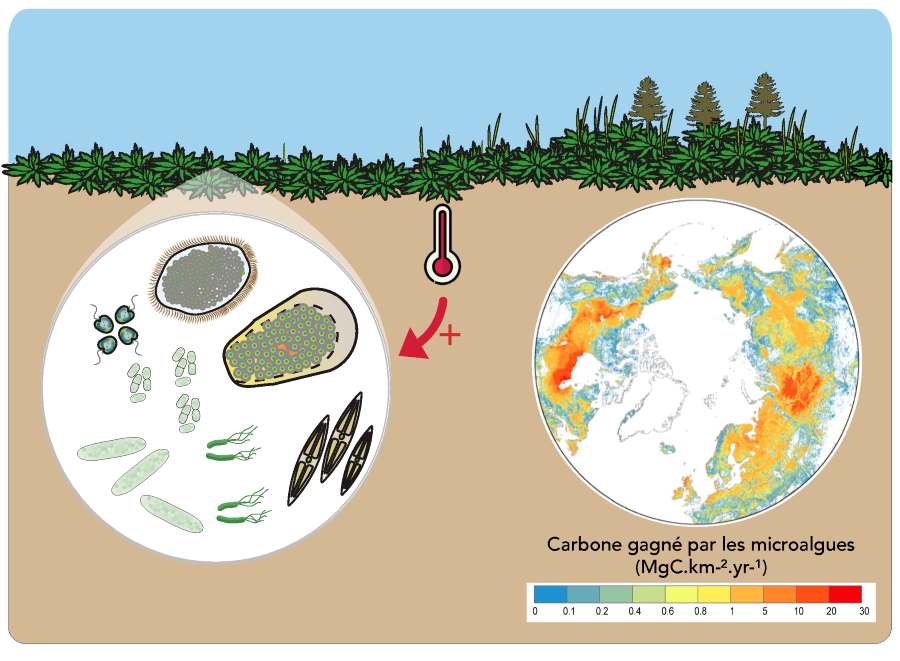

Peatlands’ potential to capture carbon upgraded as temperatures rise

According to a predictive model developed by a CNRS researcher1 and his European colleagues, the microalgae present in peat bogs could offset up to 14% of future CO2 emissions, thanks to their photosynthetic activity2. This conclusion was reached by basing the work on in situ experiments and the various predictive scenarios established by the IPCC.

It is the first model to quantify the potential compensation of future CO2 emissions by peatlands on a global scale. This result lifts the veil on a currently ambiguous section of the terrestrial carbon cycle3 and its alterations by anthropogenic climate change.

The associated study is published in Nature Climate Change.

Representing just 3% of the Earth’s land surface, peatlands contain over 30% of the carbon retained in soils4 in the form of fossilised organic matter at depth. It is estimated that this stock represents between 500 and 1000 gigatons of carbon, corresponding to 56% and 112% of the total carbon present in the Earth’s atmosphere5. While some soil micro-organisms emit CO2 through respiration, microalgae assimilate it, notably through photosynthesis. Any increase in temperature will stimulate this microbial photosynthesis, enhancing the CO2 capture potential of peatlands.

Regrettably, due to a lack of data, the mechanisms by which soil microalgae capture CO2 have not been incorporated into any climate projections to date. However, far from being negligible, this photosynthetic carbon fixation could mitigate the impact of climate change in the future.

Further work is needed – on this and other carbon assimilation processes carried out by the micro-organisms in peat bogs – to fully quantify the potential of these ecosystems as carbon sinks and improve accuracy. Nevertheless, preserving peatlands and reducing global CO2 emissions are still the best way of mitigating worsening climate change.

***

Notes:

- From the Centre de recherche sur la biodiversité et l’environnement (CRBE, CNRS/UT/IRD/Toulouse INP). ↩︎

- Photosynthesis is a phenomenon taking place within chlorophyll vegetables. Thanks to sunlight, theses plants absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and release dioxygen (O2). ↩︎

- The carbon cycle regroups all transits of molecules containing carbon between soils, air and oceans on Earth. ↩︎

- In addition to oceans, Earth soils also store large amounts of carbon naturally. It is stored there in various ways (hydrocarbons, in plants through photosynthesis, limestone rocks…) ↩︎

- According to the NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory, the atmospheric CO2 concentration in 2023 was 419,31 ppm (Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide (2025)), which is equivalent to 893 gigatons of carbon. ↩︎

Journal Reference:

Hamard, S., Planchenault, S., Walcker, R. et al., ‘Microbial photosynthesis mitigates carbon loss from northern peatlands under warming’, Nature Climate Change (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-025-02271-8

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS)

Which tree species fix the most carbon?

Forests provide many ecosystem services, including microclimate regulation, biodiversity preservation, air and water purification, and soil protection. Together with the oceans, they are one of the two most important carbon sinks, due to their capacity to store carbon in the soil and in tree biomass.

As such, promoting fast-growing trees could strengthen efforts to mitigate climate change. This raises a key question for forest managers: which tree species have the greatest mitigation potential?

INRAE and Bordeaux Sciences Agro conducted a study to identify the tree characteristics (also known as functional traits) that favour growth and thus CO2 sequestration in biomass.

The researchers coordinated an international consortium involving the French National Forest Office (ONF) and the French National Center for Private Forest Ownership (CNPF) to study the growth of 223 tree species planted in 160 experimental forests across the world (Western Europe, United States, Brazil, Ethiopia, Cameroon, South-East Asia, among others). The species were representative of all the major forest biomes.

Prevailing theory: acquisitive species grow quickly

Previous research had shown that under controlled conditions (often greenhouse experiments) species capable of efficiently acquiring resources (light, water, nutrients) generally grow quickly (e.g. maples, poplars, English oak, sessile oak). These acquisitive species have traits that help them maximize resource use (large specific leaf area, high specific root length) and improve their capacity to convert these resources into biomass (high maximum photosynthetic capacity, high nitrogen concentration in the leaves).

Meanwhile, species that are more efficient at conserving their internal resources (nutrients, water, energy) than extracting external resources are known as conservative species (e.g. fir, downy oak, holm oak) and are assumed to grow more slowly.

New understanding: conservative species grow faster in forests

However, under real-world conditions in boreal and temperate forests, the researchers showed that conservative species generally grow faster than acquisitive species. This finding can be explained by the fact that these forests are generally located in areas with unfavourable growing conditions (low soil fertility, cold or dry climate), which gives conservative species an advantage since they are better able to resist stress and manage limited resources. In tropical rainforests, where the climate is potentially more favourable to plant growth, the two types of tree species show no differences on average.

The key role of local climate and soil for species choice

Beyond general trends at the major biome scale, the researchers have shed light on the decisive role of local conditions. Growth conditions in some situations are sufficiently favourable for acquisitive species to grow faster than conservative ones. But the key is to ensure that species are adapted to their local environment.

This means that in favourable climates and fertile soils, acquisitive species such as maples and poplars will grow faster and therefore fix more carbon than conservative species such as holm oaks, downy oaks and many types of pine trees. Conversely, in unfavourable climates and poor soils, conservative species will have the greatest potential to accumulate carbon in the biomass. This recent study gives forest managers yet one more tool to help mitigate climate change.

Journal Reference:

Augusto, L., Borelle, R., Boča, A. et al., ‘Widespread slow growth of acquisitive tree species’, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08692-x

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE)

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay