Slovakia’s labour market is at a crossroads. While the unemployment rate remains low at around 5 percent, regional disparities persist. In the west, businesses struggle to find workers, while in the east and south, job seekers face a lack of opportunities. Experts say greater workforce mobility is key—yet Slovakia remains one of the least mobile labour markets in the EU.

“Workforce mobility is a critical factor in economic success,” said Jitka Kouba, marketing director at recruitment agency Grafton. This applies to both structural mobility—the movement of workers across industries—and geographical mobility, which involves relocating to different regions. “Slovakia lags behind more developed countries in both.”

The imbalance is stark. At the start of the year, the jobless rate in Bratislava was just over 3 percent, while in Prešov it exceeded 8 percent. Businesses in the west struggle with labour shortages, while workers in the east lack employment opportunities.

Slovakia has the lowest workforce mobility in the EU. In 2023, only 3.8 percent of the working-age population changed jobs, compared to an EU average of 11.7 percent.

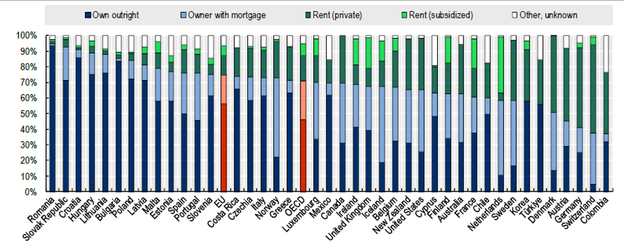

Reluctance to relocate is a major factor. A survey found that only 28 percent of Slovaks were willing to move for a job, while 33 percent would commute for an attractive offer. Housing is a key constraint—more than 90 percent of Slovaks own their home, compared to an EU average of under 60 percent.

A stronger rental market, experts say, could improve job mobility.

How Slovakia’s labour market has changed

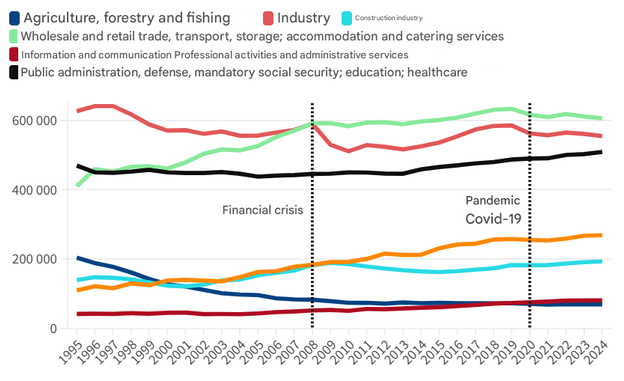

Over the past three decades, Slovakia’s labour market has transformed. When the country gained independence in 1993, more than 200,000 people worked in agriculture. Today, that figure is just a third of what it was, yet output has increased. Industrial employment has also declined, while the services sector—now the dominant employer—has expanded.

“Overall employment is at a record high,” Martin Šuster, a member of the Council for Budget Responsibility, told Denník N. “Slovakia has never had this many jobs.”

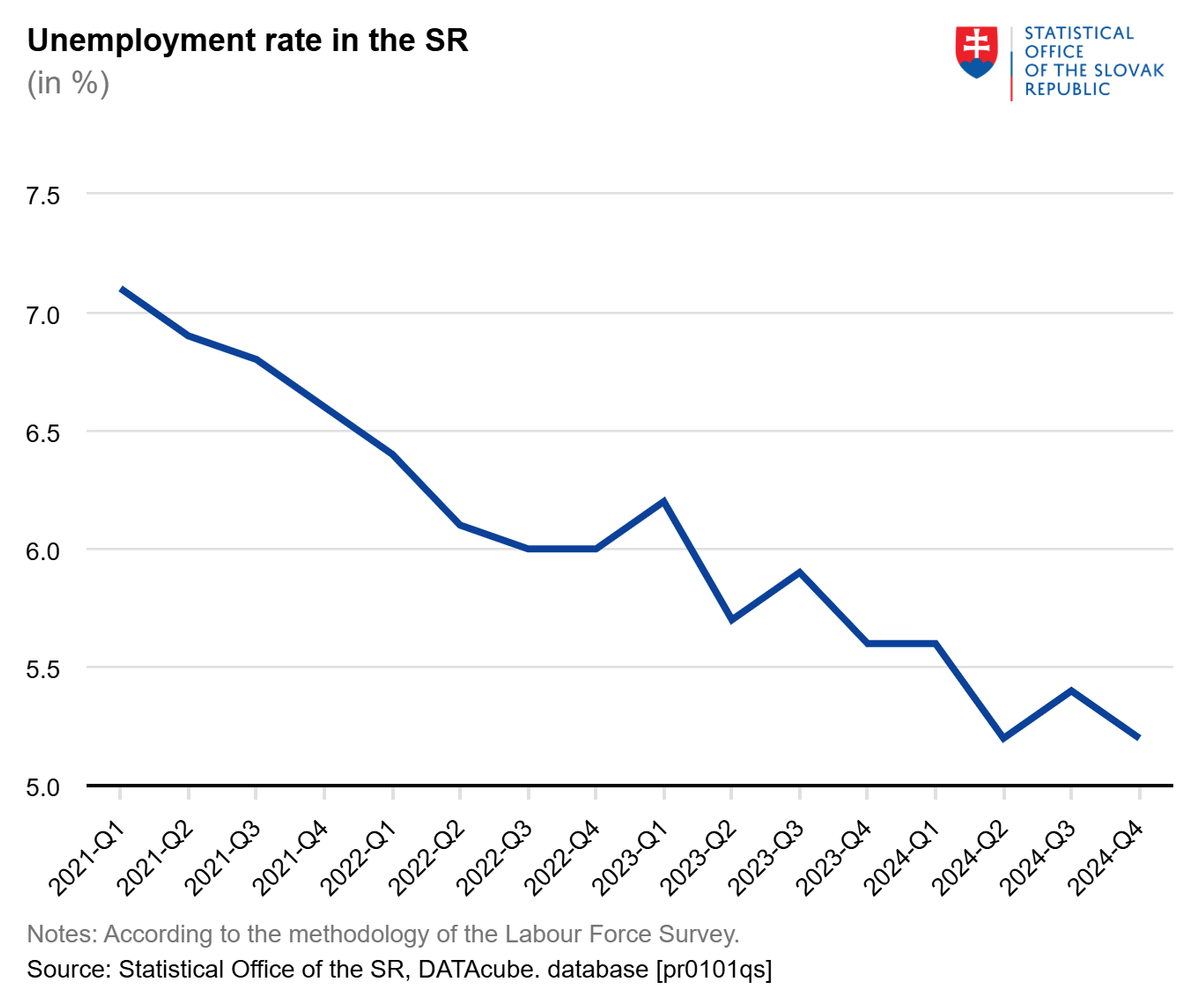

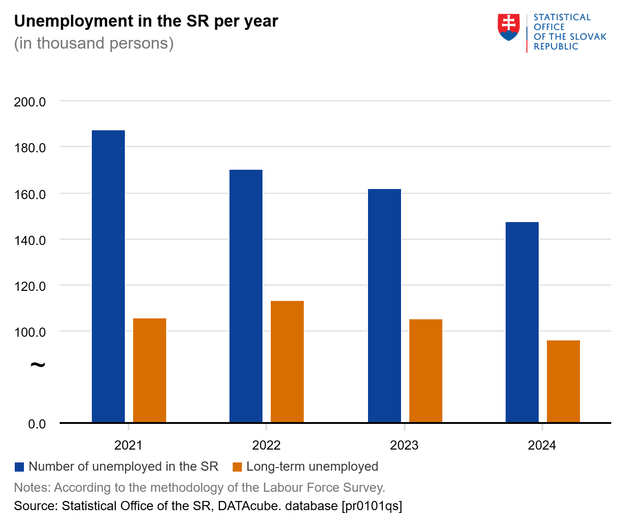

At present, 2.43 million people are employed, up from 2.1 million in 1995. Unemployment has dropped from 20 percent three decades ago to around 5 per cent today.

Services, including retail, transport, and hospitality, now employ the largest share of the workforce. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the sector has overtaken industry, growing from half to nearly two-thirds of total employment.

Three decades ago, industry employed nearly 630,000 people. The sector shrank for 15 years before briefly recovering, but recent years have seen further declines. Slovakia, however, still has a comparatively large industrial workforce.

Public sector employment has remained stable, covering state administration, schools, hospitals, the police, the military, and ŽSR, the state rail operator. Some business groups have criticised an expanding state workforce, but Šuster noted that an accounting change in 2014–2015 reclassified around 70,000 employees into the public sector.

Employment in professional and administrative services has grown by 50 percent over the past 30 years, while construction employment has risen by around 40 percent. The IT, communications, and finance sectors, though still relatively small, have doubled their workforce.

The most significant decline has been in agriculture. While only a third as many people work in the sector as they did 30 years ago, productivity has kept output stable.

“This trend has been ongoing for 150 years,” Šuster said. “Today, we need only a third of the workforce compared to three decades ago.”

Slovakia's unemployment rate (source: Statistics Office)

Slovakia's unemployment rate (source: Statistics Office)

Slovakia's unemployment rate (source: Statistics Office)

Slovakia's unemployment rate (source: Statistics Office)

The share of households by type of tenure in their residence. (source: OECD)

The share of households by type of tenure in their residence. (source: OECD)

Most Slovaks are employed in the service sector. (source: Statistics Office/Denník N)

Most Slovaks are employed in the service sector. (source: Statistics Office/Denník N)